Not necessarily the best movies ever made, but these are twenty of my favorites, in no particular order. Each post for the next twenty days will feature a brief discussion of one film (though one or two days will have multiple posts to make up for absences).

Post 11: Miller’s Crossing (1990 dir. Joel Coen & Ethan Coen)

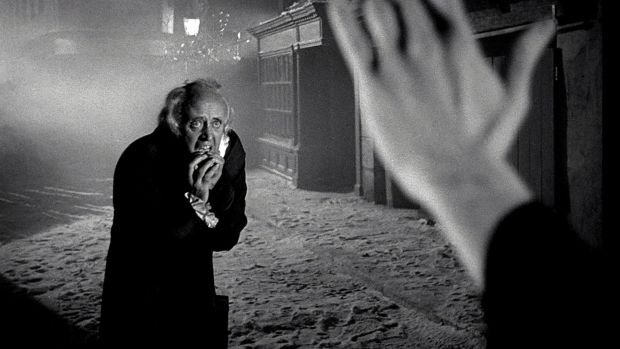

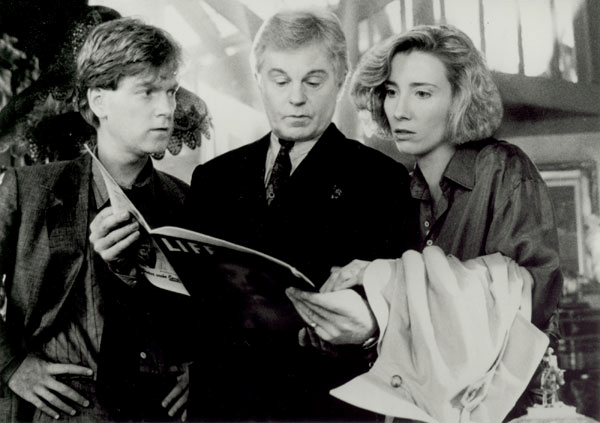

Tom Reagan’s (Gabriel Byrne) unspoken, invulnerable loneliness permeates Miller’s Crossing so much that when he finally says goodbye to Leo (Albert Finney) the camera has to move in on Tom’s face, knowing words will not come but looking for some hint as to his feelings. The image provides a heartbreaking but understandable final moment. Dialogue simply would not suffice and the image of him carefully placing his hat back on his head, longingly looking back at his long-time friend walking away for the last time, places a perfect, quiet period at the end of the film. He loves his friend, is in love with Verna (Marcia Gay Harden), but simply cannot bring himself to say the words and these relationships are now so fractured he can no longer be around either of them.

Whenever asked, I always tell anyone Miller’s Crossing is my favorite of all movies. This was the third film from the Coen Brothers, after Blood Simple (1984) and Raising Arizona (1987). Their true classics were still to come, including the perfection of Fargo (1996), the anarchy of The Big Lebowski (1998), and the haunting dread of No Country for Old Men (2007). More than anything this film is a sentimental choice for me, having first seen it at the right moment, that crossroad of adolescence and awakening maturity. Buying a ticket for one film but then sneaking into this one instead (I was 15 and it was rated R after all), I first understood that while movies tell stories, they can be about so much more than what is on the surface and it deepened my love of film as an art form.

There are moments to cherish here. There is the opening, pre-credits scene dropping us into the 1930’s contemporary dialogue; Leo’s tommy-gun ballet set to the song “Danny Boy” beautifully sung by Frank Patterson; Bernie’s (John Turturro) life pleading soliloquy about dying in the woods like a dumb animal; the hilarious discussion between Tom and “Drop” Johnson (Mario Todisco); the threatening presence of The Dane (J.E. Freeman) and his speech about “up is down, black is white”; and Tom’s last, two-word question response when Bernie asks him to once again “Look into your heart.”

A couple of technical credits cannot go unmentioned. This was Barry Sonnenfeld’s final work with the Coen’s, having done the cinematography on their prior two films as well. The photographic work at Miller’s Crossing, the titular killing forest, is particularly notable, as well as the opening credits with its reverse omnipotent POV gazing up through the forest into the overcast sky. And, of course, Carter Burwell’s score. Once you’ve heard the main theme, you know it. Often reused, just as often imitated, but never equaled, the score evokes the sadness and joy of these characters’ lives and the crescendo of unspoken emotions at work in their spirits.

A good Coen Brothers film; a great film overall; my favorite film, Miller’s Crossing (1990).