Anyone who suggests that this film is just a cynical retread of a beloved franchise solely aimed at box-office returns will probably find a lump of coal in their stocking come the morning of December 25th. It’s not a great film, but it is better than it needs to be and even gives a genuine emotional catharsis to anyone invested in the original Ghostbusters (1984). If you haven’t seen that original film, I don’t know what to tell you except there is no appreciating this one without it.

More than anything, the movie feels like a group of friends, old and new, making amends with and giving one last hug to Harold Ramis, and that alone is a worthwhile, honorable reason to see it. Ramis was a motion picture comedic genius and his influence on American culture cannot be overstated. Afterlife is an homage to not only Ramis, but also the Steven Spielberg/Richard Donner adventure films of the 1970’s & 1980’s. Imagine if the Goonies (1985) and E.T. (1982) had a love child raised by Superman (1978) and you begin to understand Jason Reitman’s approach to this material.

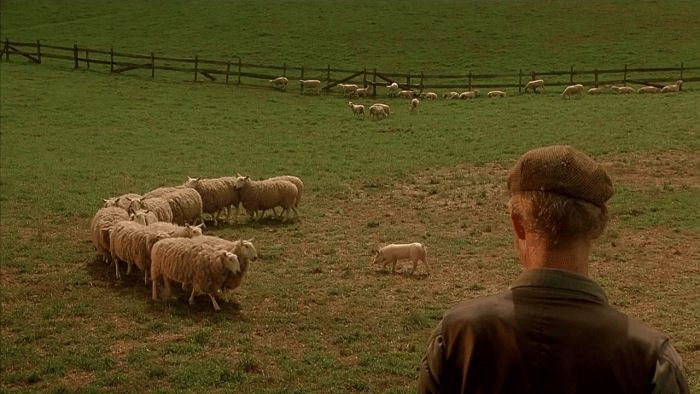

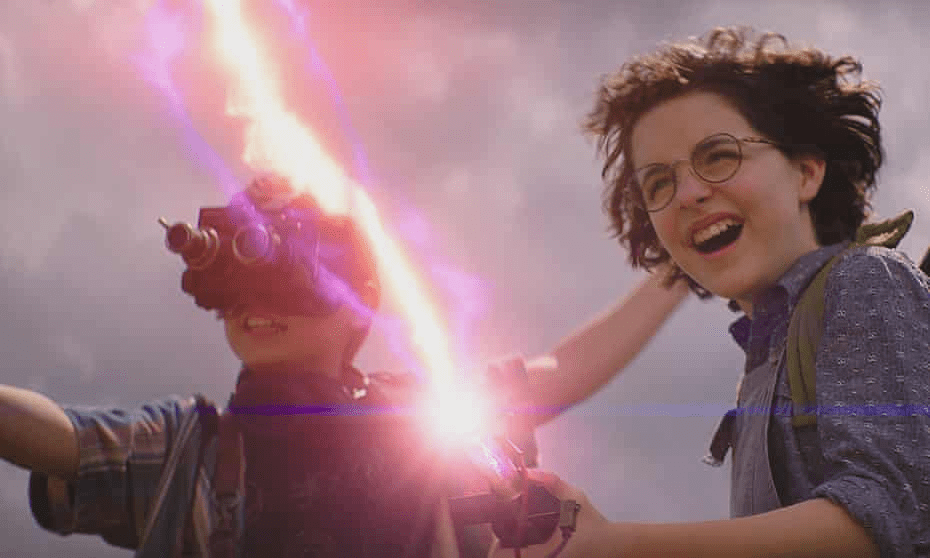

When their estranged grandfather passes away, adolescent siblings Phoebe (McKenna Grace) and Trevor (Finn Wolfhard) move into his neglected farmhouse in Oklahoma with their mother, Callie (Carrie Coon) only to slowly discover that not only was their grandfather one of the original Ghostbusters, but he also was patiently guarding an apocalyptic secret. In Oklahoma they befriend Podcast (Logan Kim), Lucky (Celeste O’Connor), and Gary Grooberson (Paul Rudd) all of whom will, of course, play a part in the final confrontation with the ghosts and demons.

I chuckled a lot and laughed out loud at least once (the suicidal anarchy of the miniature Stay-Puft Marshmallow men has to be seen to be appreciated). Grace is a real standout as the film’s true protagonist. She finds the right balance between unemotional sarcasm and the wonderment of discovery as she solves the mystery of her family’s legacy. And Kim has a fun time as her only friend and constant podcaster. Wolfhard is under-utilized and I wish a lot more had been done with Ivo Shandor (J.K. Simmons) and his backstory/involvement with Gozar (Olivia Wilde). Simmons is there…and then, too suddenly, he’s gone. Maybe his exit was supposed to be funny? I don’t know, but it just doesn’t work.

What does work is the overall nostalgia, not sentimentalism, building to the film’s Harry Potter-esque finale. I saw the original in theaters in 1984 as well as the fun, but disappointing, sequel in 1989. I sincerely enjoyed the non-canon 2016 film, entirely ignored here, with its talented cast. Ghostbusters: Afterlife, appropriately titled and the best of the sequels, is about unfinished business and confidently tells its story while giving the audience a lot of reason to smile.